Letter from Plonsk, a city in northern Poland, May 30, 1812: “Dad, soon I'll see you in the cafe, avidly reading the bulletins that will contain the great deeds of the 'Grande Armée'. You will rejoice in my victories and say: 'My son was there.' God will not abandon me and will watch over me amid the bristling bayonets that will tear my chest, but don't worry, the war won't be long. A good fight and we're headed for St. Petersburg. He thinks that instead of forty thousand Poles that the emperor thought he was going to get here, there are one hundred thousand who have left their home to serve.

With less than a month to go until Napoleon's first regiments crossed the Neman River, Fauvel, a soldier who counted the 615.000 who took part in that mammoth conquest, tried to reassure a family miles away. An unknown official who, however, did not know that he was not going to return home, nor to hug his parents again and that, of course, would not be mentioned in any history book. If he could have seen the future, he surely would have preferred, even, to be killed before, instead of suffering that slow agony of strenuous marches, torture, cambre, disease and extreme cold. His ignorance helped keep her spirits up. "We will enter Russia and we will have to stick around a bit to open the way and continue calmly," a grenadier named Delvau also wrote to his family, confident.

It was still well fed, had a heated floor, and was commanded by a 42-year-old Napoleon who never looked very good. In the previous decade he had staged a series of dazzling military feats in Italy, France, and Egypt, been crowned at Notre Dame, and continued his astonishing string of victories at Austerlitz, Jena, and Friedland. In the summer of 1812, he ruled the entire continent from the Atlantic to the Neman River... but beyond that, nothing. He held out the vast region of Russia, soon as he set out to conquer and extend his dominance to Asia.

His Army was so large that it took him eight days at the end of June to cross the river. There were Italians, Poles, Portuguese, Bavarians, Croatians, Dalmatians, Danes, Dutch, Neapolitans, Germans, Saxons, Swiss... In total, twenty nations, each with their uniform and their songs. The English were the third part. Not since the time of Xerxes had such a considerable force been seen. It was a huge itinerant city that consumed food voraciously and destroyed everything in its path.

An episode from Napoleon's Russian campaign, painted by Philippoteaux ARMY MUSEUM

thirty thousand vehicles

Each division was followed by a ten-kilometre column of supplies with cattle, wagons loaded with wheat, masons building ovens, bakers, twenty-eight million bottles of wine, a thousand cannons, and three times as many ammunition wagons. Also ambulances, stretcher-bearers, blood hospitals and teams to erect bridges. The chiefs have their own carriage and sometimes one or two other wagons to carry bedding, books, and maps. They totaled thirty thousand vehicles and fifty thousand horses.

In short: it was an untenable army and Bonaparte had been on the march for several weeks when his men realized that he had only conquered a void. Tsar Alexander I's brilliant strategy of retreat and scorched earth forced the Corsican to pursue for miles and miles, desperate, in search of a decisive battle, but nothing. Whenever he arrived at a village, he found it burnt down, without inhabitants and with the food buried.

On the 7th he finally had his long-awaited and bloody confrontation at Borodino, where his surgeon amputated two hundred members with the only help of a napkin and a quick drink of brandy. The Russians had 44.000 casualties and the French 33.000. From an arithmetic point of view, France won, but Napoleon considered it a crash to the loser to the lotuses of his generals.

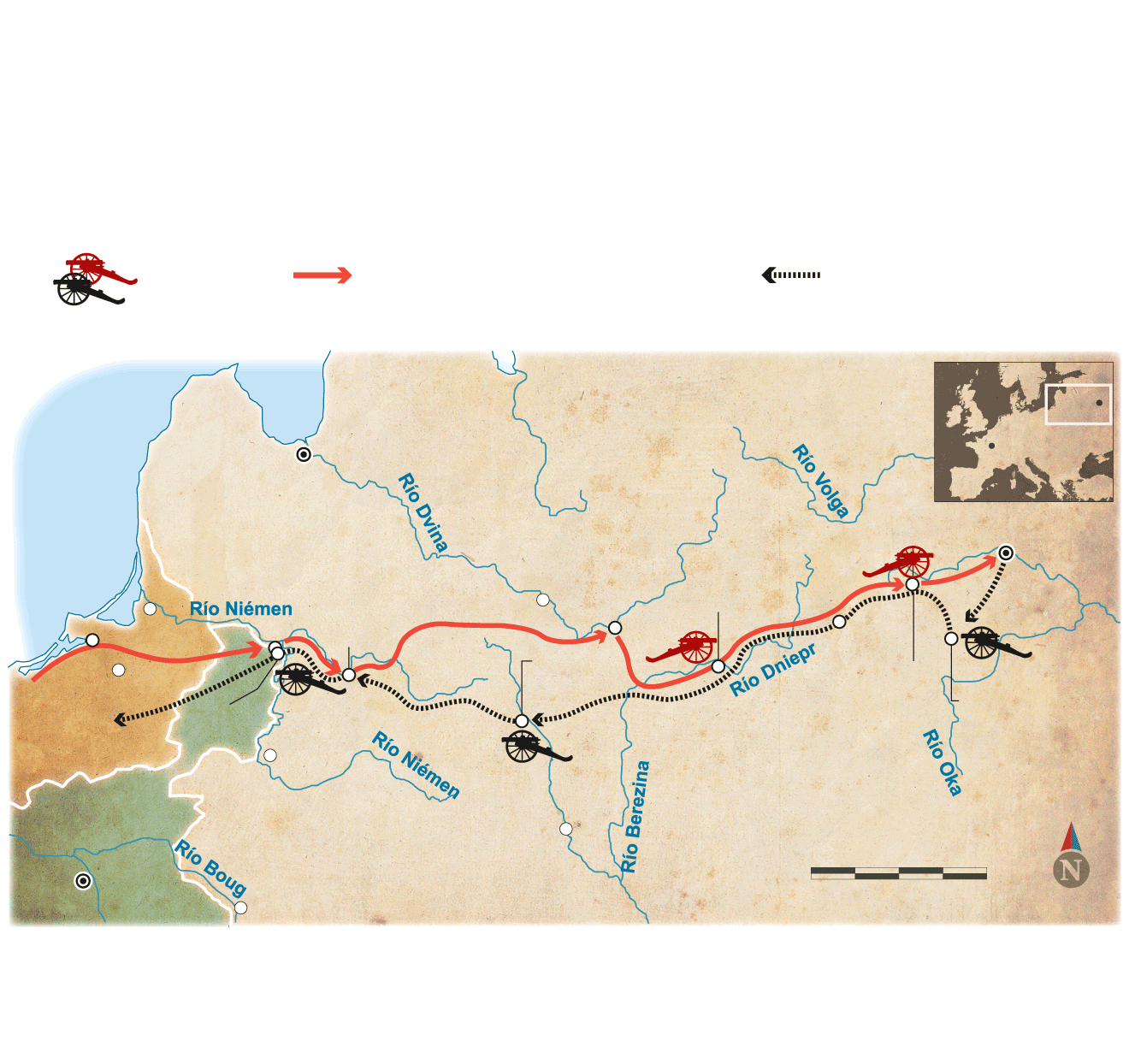

The Napoleonic invasion of Russia in 1812

On June 24, 1812, Napoleon's Grand Army, made up of 615.000 men,

They undertake the invasion of the Russian Empire. Of the total number of soldiers who left, only

less than twenty percent returned. Russian victory over the army

Spain was the turning point of the Napoleonic wars

troop withdrawal route

French to Prussia

tour of the troops

from Napoleon to Moscow

MOSCOW

(September 14/

October 19)

maloyaroslavets

(24 of October)

Source: self made /

P. SANCHEZ / ABC

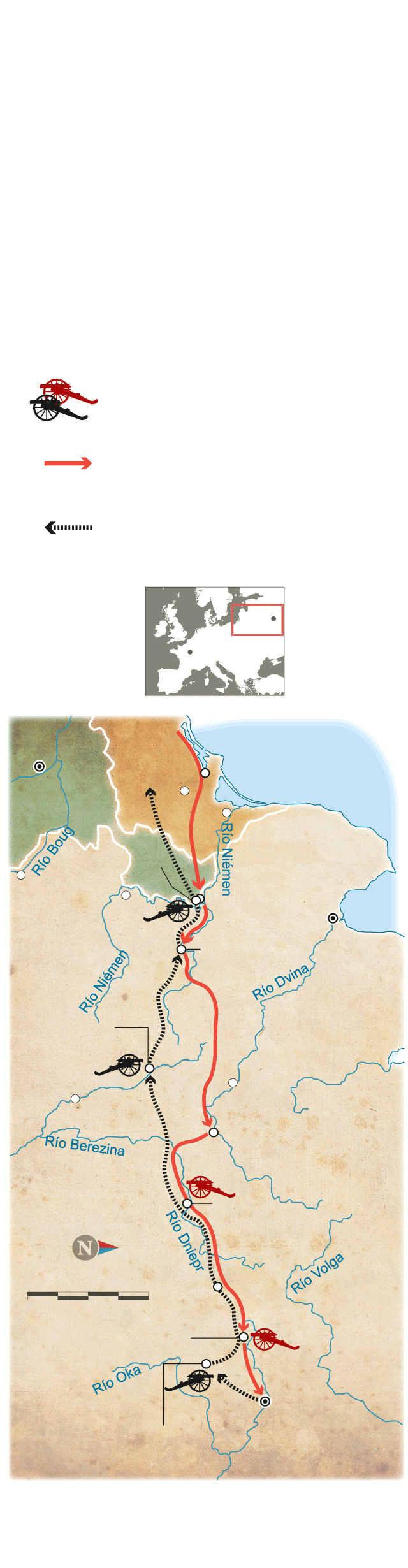

The invasion

Napoleonic of

Russia of 1812

On June 24, 1812, the Great Army of

Napoleon made up of 615.000 men,

They undertake the invasion of the Russian Empire.

Of the total number of soldiers who left, only

less than twenty returned

percent. Russian victory over the army

English was the turning point

Napoleonic wars

troop withdrawal route

French to Prussia

tour of the troops

from Napoleon to Moscow

MOSCOW

(September 14/October 19)

maloyaroslavets

(24 of October)

Source: self made /

P. SANCHEZ / ABC

Finally in Moscow

On the afternoon of Sunday, September 14, the 'Great Army' came to the outskirts of Moscow and the emperor suffered on the hill to watch the spectacle. “Here it is, finally! About time,” he exclaimed. Joy, however, appeared little to him, when he realized that no one came out to receive him with the keys to the city on a velvet cushion. Of 250.000 inhabitants, only 15.000, mostly beggars and criminals released by the tsar and armed with gunpowder to set fire to the buildings. "We walked between burning walls," lamented a Napoleonic soldier.

On the same day, Brigadier General Jean Louis Chrétien Carrière will refer in his correspondence from Moscow to the attitude of Napoleon, who delayed his return for a month, convinced that the Tsar would appear asking him to negotiate peace. “My lovely wife, we have been in the same position for eight days. We are confined and the season is already very cold. Winter will be hard." But Alexander I gave no sign of life and the frustrated emperor would possibly return to Paris on October 19, with the temperatures falling.

That same day, a commissary employee named Lamy warned his parents that all the land as far as Smolensk was burned and that "the horses will starve." The most terrible part began, the one that already had the most terrifying testimonies on the maps of the 90.000 infantry men and 15.000 surviving cavalry, with their ten thousand carts of food for twenty days.

Sleep them and slit their throats

On November 6 the thermometer plummeted to 22° below zero and the sheepskin neufs proved insufficient. The peasants, moreover, received the order to give shelter to the invaders and serviles a lot of brandy, to slit their throats when they fell asleep. An English observer of Kutuzov saw "sixty naked and dying men, their necks propped against a tree, whom the Russians beat with a stick to split their heads while they sang."

The struggle to eat and find shelter was now the only thing that mattered. At dusk, the men gutted the dead horses to get inside and get warm. Others ingested the clotted blood and, as soon as a companion died, they took away his boots and the little food he had in his backpack. “Compassion descends to the bottom of our hearts because of the cold. The soldiers know that there is plenty to eat on the left and right of the road, but they are rejected by the Cossacks, who know that all they have to do is let General Winter do the killing,” wrote another soldier.

Of the 96.000 men who survived the Battle of Maloyaroslavets on October 24, only 50.000 entered Smolensk nine days later, and that was half the way back. The temperature dropped is 30° below zero and the muskets hit the hands. British General Robert Wilson spoke of "thousands of missing, naked dying, cannibals and skeletons of ten thousand horses cut to pieces before they died." “When leaving this city –Captain Rodent added in another letter–, a great crowd of frozen people has remained in the streets. Many have gone to bed so they can freeze. One walks on them with lethargic feelings”.

Oil on canvas by the painter Adolph Northen, in his painting entitled 'Napoleon's Retreat from Russia'

"Fool me"

Solidarity and discipline within the army disappeared on the way to Vilnius. In fact, Napoleon abandoned his soldiers in Smorgon to return to Paris as soon as possible and form a new government to stop the coup that was being woven behind his back. His sled set off at full speed on December 5 and, shivering with cold on the way, he confessed to General Armand de Caulaincourt: “I was wrong not to leave Moscow a week after entering. He thought that he would be able to make peace and that the Russians were looking forward to it. They fooled me and I fooled myself."

Of the six hundred thousand men who crossed the Niemen in June, only a few tens of miles made it out of Russia with their lives in December. Less than twenty percent. Fauvel's parents waited for his son for months, until in May they received a letter signed by Lieutenant Joseph Lemaire: “Sir, I have the honor to announce that I was taken prisoner on December 25 with his son. It is with sadness that I also announce that I saw him die by my side. Lieutenant Colpin seized before the cross from him and this portrait that he sent them.